FAR FROM KANSAS

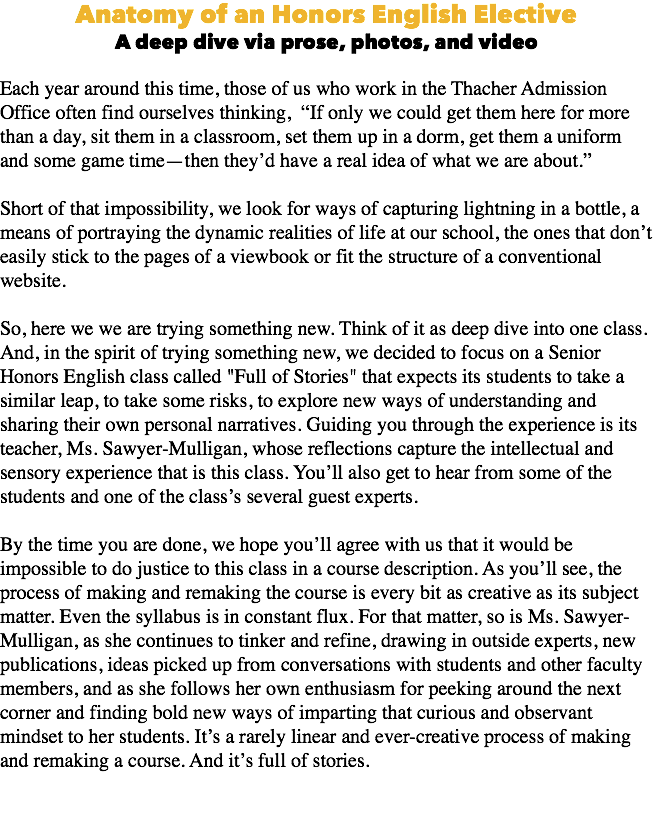

My offering is still morphing in content and form even as my dozen seniors take their seats around the big oak oval. I’ll take many cues from them along the way of this writing journey. And they’ll quickly see that, despite the familiarity of the smells and sights of Room C, they’re not in Kansas anymore.

NAME CHANGE

This year, I tweaked the title of the course from Turning Toward Home to Full of Stories–a nod to author Natalie Goldberg’s notion in Writing Down the Bones: “Writing comes out of a relationship with your life. You are full of stories waiting for release.” I wanted to start from the idea that we don’t need to go looking for stories to tell as much as be open to remembering–and then shaping–what we already know. I wanted to be the parent in Richard Wilbur’s The Writer, who, finding a starling trapped in his daughter’s room, steals in, “lift[s] the sash,” backs out, and then watches, not interfering further, as “the sleek, wild, dark/ And iridescent” bird stops “batter[ing] against the brilliance,” eventually to find the open window.

I knew that once these students found the well, it would never be empty, no matter how many buckets they hauled up. I also knew that by Week 3 or even 2, they’d nail me for a mixed metaphor.

FIRST DAYS

It’s getting-to-know-you time. Actually, we already know each other, at least a little: Ben’s been one of my first Open House customers at the kitchen counter since he first arrived at Thacher. Kennedy, Megan, and Mitch were in one of my English 1 sections back in the day; Inga and I were advisee-advisor her sophomore year (ditto Kennedy); Orren and I have connected over our Merrimack River roots since we first met; David was at the house for Fireside Study every Thursday night last year as one of Michael’s advisees. Stella and I kicked up dust together hiking the last part of the trail to Golden Trout Camp her first September at Thacher. Manny, John, Kevin, and Kami–four I’ve watched on sports fields and courts, in performances, around campus forever. Of course, they’ve been thick in each other’s lives all this time, so we are starting in a place of familiarity and, I can already see, even fondness among the participants. (This will be important when we share our stories.)

On our first day together, I lay out the informing ideas of the course, among them, the hope that they will trust their stories are “all right here, right here at home” (Patagonia Surf Ambassador Dan Malloy, speaking to the School just before fall camping trips last year) and that, with the narrator of Mark Haddon’s The Curious Incident of the Dog in the Nighttime (Chapter 181) as an extreme model of attunement, they will come to “see [more of] everything” around them: internal and external sensitization. I pass out Field Trips Notes-books and send them out the door for the final ten minutes of class. They take seats along the expanse of stone steps or on the interjecting boulders, their backs to Study Hall and Old Main, their faces west. They take notes on what they see. Simple. A first step on the “I see everything” yellow-brick road.

READER READING

As prompts for remembering their own stories, or conduits to universal themes, we tuck into the Full of Stories Reader off and on during our first weeks. An anthology I’ve assembled and reassembled annually, it contains one- or two-page essays by published authors, one-offs in the “Lives” column of The New York Times by writers young and old, excerpts from longer memoirs, pieces written by students in this course in prior years, many of whom the present seniors know. “This is Teo who graduated last year?” Yes. “Wait! Is this the same Connor Schryver?” Yes. In a real book, in their own hands, they see proof of what they just read in Goldberg (“First thoughts are powerful”) and what they will come to know: There is no good writing, only good rewriting.

The Reader’s chapters–“Homeground,” “Parents,” “Siblings,” “Extended Family,” “Schoolcampfriendscrushesloves,” etc.–move in and out of attraction, personal connection, and complexity for each of the kids in fresh and unpredictable ways for me. We often break into smaller discussion units according to their druthers. As often, I move completely away from the Harkness table to take notes on their discussion. They are free in their opinions, their likes and dislikes; they lean in to listen to each other. They are quick to drill to the essence, as Megan did in an early discussion: “The question ‘Who are you?’ becomes ‘Who am I?’ really clearly here.” We count on Mitch for the minority opinion and Manny to help him understand the majority view; we look to David and Kevin for clarity, Kami and Inga for a unique sensitivity to the text. Not a week into the course, all embrace with stunning maturity the cognitive dissonance presented in the juxtaposition of Reynolds Price’s A Day in the Life of a Porch (the warm, honeyed safety of one family) and David Mamet’s The Rake (the raw danger and lasting pain of another). They set to drawing their homes on graph paper, overlaying it with tracing paper to demonstrate graphically how people in families inhabit spaces in relation to one another. Ben asks a logical question about our purpose. John works in flurries and stops. Kennedy is focus incarnate; Stella roots around thoughtfully in her sneaker pencil case for just the right instrument; Orren, wanting to get it “right,” asks for a little more direction. Then he catches on: there is no right. There is only his truth in this moment.

All twelve are propelled by the Reader essays (later by Alexandra Fuller’s Don’t Let’s Go to the Dogs Tonight and Mark Spragg’s Where Rivers Change Direction) into their own stories, some that make me laugh or gasp in surprise, some that strike me hard or knot up my heart, knowing the courage it took to write them. All need reworking, but that’s the point: It’s all fodder for a possible revision at term-end.

INTO THE FIELD

Attunement–seeing, hearing, touching, smelling. Letting those sensory inputs prompt memories. Letting those memories become stories. This is why we take “I see everything” Field Trips. The first major one involves rousting the troops before dawn to walk quietly to the far edge of our trampled world (horse hooves), where, past all the riding arenas and fields, past the cow pen, the Hoyt-Isaacson trail switchbacks up the bony shoulders of the Los Padres foothills. Everyone finds a spot to observe the Valley lightening with the coming sun, coming to life in sound and movement. They take notes.

Trips in later weeks will again unplug them from the classroom and push them onto other “observation decks”: behind the scenes in the kitchen, the horseshoeing barn, the vehicle maintenance shop, a faculty home, where part of the Buildings and Grounds crew are clearing gutters. They’ll go to a part of the Library they’ve walked past a thousand times but never entered–the Archives, where they’ll poke around, seeking some visceral connection with a past they are continuous with but don’t often think about explicitly. They prepared by reading Barreda Sherman’s Memoirs of an Old Boy, a chronicle of Life@Thach a century ago. In our last week, as part of Portfolio, they will land at the heart of the School, the Pergola, each to write her or his own “slice” of Thacher from a compass point of choice. A few weeks later, I’ll put them together, starting with north and collating the essays by degrees, moving around the points of the compass. These will form one chapter of a book made of stories they’ll chose from their oeuvres, which I’ll copy and have bound for each writer. We’ll probably sign them like yearbooks, and we’ll stash one copy in the Archives. It’ll be there when they come back for Reunions, which right now seem too far in the future even to contemplate.

FEEDBACK LOOPS

An essay every week, returned with a page or more of commentary, but no grade. It might feel like walking off a short cliff after years of write-a-paper-get-a-grade-write-a-paper-get-a-grade, but it’s not long before most are OK with this change. Instead of grades, I want to make substantive responses to these writers’ weekly pieces quick and easy, accessible feedback loops–as well as substantive responses to their writing. So I create for each a running GoogleDoc on which I cheerlead, poke and prod with questions, berate gently for repeated errors, make concrete suggestions for the big project down the line–(pre)Portfolio at the end of Trimester 1 and Portfolio at the bittersweet very end. Because this document is an evolving document and electronic, each student’s individual threads of success and work-to-be-done can’t get lost in the great shuffle of time and task that is Thacher life.

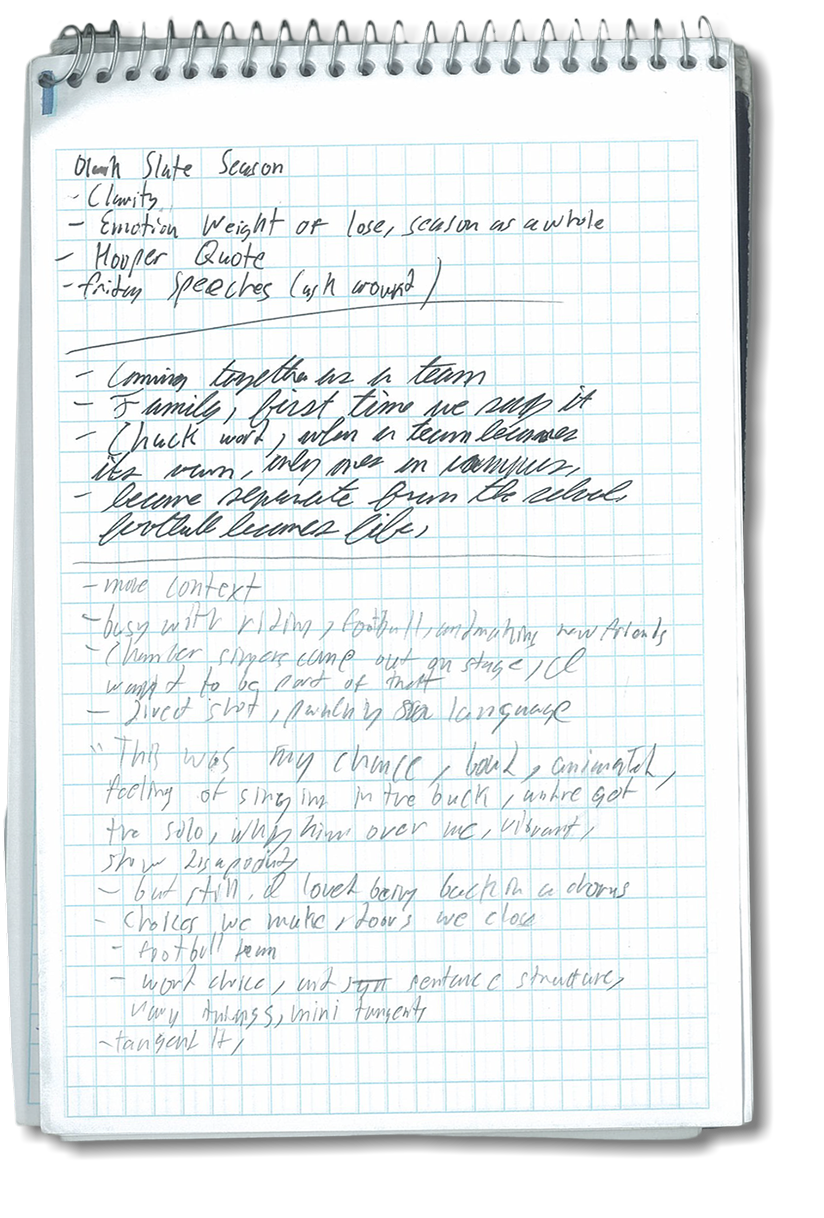

METEORITE

The other important feedback loop starts in each student’s hands. After they’re warmed up by one or two essays in September, I ask them to add a short reflection–a meta-write–at the end of their pieces answering some questions about their thought and writing process: Why did you choose the prompt you did? What was your intention, or your hope for this essay? What did you want to focus on in content and expression? What were the challenges? The easy parts? Why, do you think? What, if anything, in your WFFfb [Writing for Friday feedback] did you consciously pay attention to as you wrote or rewrote? Is this a piece you might want to return to in Portfolio?

Right away, this class adopted an in-joke from last year’s class–a student who thought the word I was using was “meteorite” (which made an interesting kind of sense, if you think about it). But that was so last year when, in dictating some feedback comments for this gang, my software provided several other alternatives: “Mr. Right,” “never the right,” “next to write,” “now to write,” “that’s right,” “matter right.”

Eventually, it spat out the phrase I didn’t know I’d been waiting for: “Meant-to-write.”

WORKBENCH

Every other week, we devote a full class to Writers’ Workshop–a time for me to share principles of narrative writing that we haven’t formally covered in our discussions, to give prompts for quick-writes and to look closely at examples of effective writing from their pieces–each student’s work up for praise, which we call The Mutual Admiration Society. The whole 40 minutes is interactive, with each student moving between his/her laptop and the Smartboard. They talk about what makes a paragraph, sentence, or even a phrase work for them as receivers. Sometimes we agree, but often, their observations of each other’s strengths open my eyes wider. Then I present an anonymous sentence or paragraph, one that needs expansion or greater specificity, perhaps structural revision. They play with it independently of one another, then they read their new versions aloud. They enjoy the activity–probably because it’s fairly novel for them, just plain fun:

I prompt: “You finally return your mom’s text by calling her. Write the dialogue. Go!”

Or we all look at a paragraph from one of last week’s submitted essays:

About halfway through, an argument somehow broke out. We yelled at each other and then began to fight. Most boys just pushed each other around, and it didn’t seem to be too serious. [Then], suddenly, I felt a basketball come whizzing by my head and slam against the wall.

“You almost took me all the way there in this paragraph. Now, all of you: expand the innards to elongate the set-up to the basketball. Go!”

Or, I ask, “How do you capture a voice in letters on the page? Talk like Mr. Duykaerts when he’s explaining how to pick a horse’s hoof. Go!”

By their third essay, small changes in their prose here and there tell me that most of them are growing more attuned to the relationship between content and form. The essays are clearer, truer, more fluid and forceful than the first and second. How much can I attribute to Writers’ Workshop? How much is simply a matter of chipping the summer rust off? I won’t have data on this until the class has filled out Course Evaluations in December, but I’m banking on WW having something to do with their loosening, their greater sense of play and experimentation, their better writing with practically each week flying by.

STREET CRED

At least once a term, I bore myself. I leave class dissatisfied, unhappy with what went on–or, more likely didn’t go on. That’s when I’m glad for the guest coming along in the syllabus. This year’s line-up: Alice Meyer (Psychology teacher at Thacher, to speak on the nature of memory), writer/filmmaker Melissa Johnson (once in October, again in November), and writer/filmmaker Scott Frank. Mrs. Meyer tells us about false memory, flashbulb memory, pulls out some interactivity on encoding, retrieving, finding memories. All of it snakes its way into many random moments afterwards–useful, informative stuff that keeps us wondering about the intersection of the “real” and the “true.” What Melissa brings–a willingness to ask hard questions about the moving target of identity and to workshop with the students on their essays–is a different kind of gift. She’s a rock star to them–young, hip, a published author and award-winning filmmaker who’s dropped in from Venice Beach to affirm the work they’ve taken on in this class. We’re in their favorite Reader “chapter” so far–talking and writing about the rules of engagement in young love, about being caught between a rock and a hard place in relationships, about the ongoing cost/benefit analysis of adolescent social decision making–which makes her presence all the brighter. They’re writer-writes-on-rites-of-passage groupies before she’s said three words; they “l-o-o-o-o-o-v-e” working with her. Their begging is insistent enough that I empty the coffers to secure a return engagement.

By the time Scott Frank comes for his two days with us (among his credits, Get Shorty, Minority Report, The Lookout, The Interpreter, The Wolverine, A Walk Among the Tombstones–and serving for many years as artistic director of the Sundance January Screenwriters Lab), the students know how to make the most of their time with luminaries. They ask great questions (“How do you know when a story is over?”), they listen with obvious attention, they scribble notes on Scott’s answers. I want to stand and cheer when he says, “Cut anything that sounds like writing.” Then I actually do (but sit quickly back down and shut my mouth just before it’s too late) when he says, “If you pay attention, you start to see things. You hear conversations. You’re always on the make for those things that are a piece of a story yet to be told.” He is a field trip unto himself.

PORTFOLIO

We had a dry run for this project back in November–the (pre)Portfolio. Between then and now, though, the students completed course evaluations, a helpful tool for all of us faculty aiming to refine their courses as we go. Their suggestions about laying the project out clearly much earlier in the term, about building in more peer consults and editing, and about our collaborative use of the WFFfb documents have informed how I’ve structured the week. Conferences are required as a kick-off moment–20-minute one-on-ones to talk turkey on the work ahead. They prepare by sifting through their pieces for ones they genuinely want to return to. They bring specific questions about their ideas, their structures, their imagery.

John has a hard time separating his wheat from his something-more-than-chaff-but-not-so-much-wheat. He brings five essays to the conference and together we talk through the challenges and opportunities each would pose. He finally whittles down his stack. Both Manny and Stella, independent of each other, have a strong impulse to combine two pieces into one. Both involve Thacher camping trips that, as the most memorable ones do, veer close to catastrophe. Megan switches horses mid-stream, deciding to return to WFF1 (written in September); she’s a very capable rider-writer, though, so I just give her a thumbs-up and send her loping off. Kami’s going back to a riveting piece that partners a personal story with razor-edged social commentary. Kevin will talk with his older brother about additional detail in an essay about fraternal adventure. Inga finds a new complication in one of the pieces she wants to revise; we lay out possibilities for its resolution. Kennedy, Orren, David, and Mitch are keen on solving the narrative and tonal complexities of The Applicant–a prompt that started with a look at the application photos of themselves (8th graders, all), moved to reading photocopied parts of their application essays and short answers, and ended with a piece of writing. How can I be both selves–the me of then and the me of now–and keep the essay coherent? Ben asks for a second meeting, and, though it’s like untangling a Gordian knot to find a free slice of time we share, we finally do, on Sunday night. What he quietly presents me with–maybe for Portfolio, maybe not–is so powerful it leaves me without words of any kind. Ironic.

The work-week goes by and Portfolios stack up on my front porch bench. I bring them in and pile them on my desk. It’s raining as I stare at the folders. There’s a knock on the door, and I get up to find John, pulling his Portfolio out from under his wet hoodie. “It’s pretty thick now,” he grins, placing it carefully in my hands: special delivery. He’s right. What were sleek, dark, flat, empty laminated folders back in September are now falling apart at their seams, bursting with stories. I return to my desk and top the stack with this last one.

I’m not yet ready to dive in, so I fiddle with desky things, lining up the stapler next to the phone, neatening the paper piles. I glance at my “Forgotten English” word-a-day calendar. Strengthy, meaning “forcible; strong.” Never heard of it. I rip off that page and, four sheets later (I’m weeks behind), find a word I’ve always loved: palimpsest: a manuscript that has been written upon twice, the first writing having been rubbed off to make room for the second. I introduced it to this class months back when we were talking about revision. The word, I know, is also defined as “something having usually diverse layers or aspects visible beneath the surface.” I think: a perfect metaphor for what we’ve been about all these weeks–each writer’s first story, the variegated layers added by multiple forms of feedback and time away, the revision that doesn’t actually wipe clean the initial try, but gives it foundation and texture.

NEVER CAN SAY GOODBYE

As of last year, what was a 20-week course has ceded 3.5 weeks to Senior Exhibition research and writing–something initiated by the English Department. While I believe we absolutely should give the seniors the time they need for SrEx, I’m feeling the loss of what we used to do in that final month of Turning Toward Home. So I’ve thrown a new elective into the Spring Trimester offerings: Writing Thacher: The Power of Place. In a variation of wanting my cake and to eat it, too (a phrase I’ve never quite understood), I want more cake for whoever of this little writing family we’ve made also wants more. We’ll see if anyone bites.

WHAT WE WANT

Back to Richard Wilbur’s narrator in The Writer. As he listens to his daughter clacking away on her typewriter, “writing a story,” he thinks of her as both captain and crew of her own ship, the noise of her artistic progress “like chain hauled over a gunwale.” He wishes for her “a lucky passage.” That’s what I want for each of these twelve sailors, too–not an easy go of it, but one in which they come to know they have the strength to haul anchor, the guts to set a course, and the grit to keep going when the skies go inky and smooth seas turn to chop. (And here, they’d call me out on a cheesy cliché, just as Wilbur’s narrator imagines his daughter would.)

But clichéd or not, it’s what we all want for our students, we teachers--and, reductio ad logicam, maybe all we want.

About the Author

In addition to teaching English to freshmen and seniors, Joy Sawyer-Mulligan advises sophomore girls and occasionally contributes writing and photography to Thacher publications. On Saturday nights you can almost always find her stirring the cheese dip and baking her famous chocolate-chip cookies for the all-school Open Houses that rock the rafters of the rambling redwood house on campus she shares with Michael, her husband (also Thacher’s Head of School).